A Foreword to the Future

“Forgetting photography” means understanding the afterlife of the medium and rethinking “the visual in culture, science, technologies”.1 So argues Andrew Dewdney in his provocatively titled Forget Photography (2021). Photography is, Dewdney suggests, irrevocably not what it once was. Its forms of production and its modes of consumption have changed forever, and the very term "photography”, he writes, has become "a barrier to understanding the altered state of the default visual image”. Dewdney proposes to critically forget and then re-imagine photography as a networked image. Even though this might be a challenge, this “forgetting” of photography—which would imply a different way of organising knowledge about the visual in culture—can help to do justice to current complexities: how the image functions, how it is made, and how it is seen in the present moment.2

The International Centre for the Image, opened last July in Ireland, at Dublin’s north Docklands, creates a space for forgetting and rethinking photography as image. A multipurpose space, with a library, artists’ studio spaces and a bookshop—at its core is an exhibition space which seeks to be a hub for rethinking, and taking critical and artistic control of the image.

Foreword, the inaugural exhibition of the new International Centre for the Image exemplifies and points the way to what the multifarious futures of photography and the image might be. As photography has gradually, and then dramatically, dematerialised into the digital image, its practitioners have remade its possibilities through accelerating the formal changes which are taking place via the digital, by ironically playing with those processes of change, or by knowingly reversing them. Photographers and image makers forget photography by remembering it anew, with astringency, irony, critique, obliquity and deliberative nostalgia.

Entering the Foreword exhibition space in the International Centre for the Image, Alan Butler’s piece One Hundred Years of Solitude is immediately indicative of the critical energy which characterises this exhibition. This series is a melding of processes (wet-plate collodion) from the origins of photography with the landscapes of video games, and yet those video game landscapes are themselves a circling back to Carleton Watkins’ images of the American landscape, in particular Yosemite National Park. Watkins’ Eden-ising of Yosemite followed hard on the heels of the expulsion of the Native American populations from the area, and so the idea of the United States, which is displayed via an aesthetics of landscape grandeur in Watkins’ images, goes hand-in-hand with the barbarism which enables it. Butler is able to layer into his works a visual nostalgia which, in its unreality, calls attention to its own disjunction–Butler’s landscapes, each differently, call on the imaginary spaces of video games, which (like Red Dead Redemption) are shown to be caught in a loop of visual and ideological backwards-look.

The fusing of anachronistic visual modes, which drives Butler’s work, also animates Colin Martin’s Unreal Apocalypse (see image at the top of this page), paintings which replicate software-generated landscapes made in online communities. As with Martin’s previous work, the interest here is in formally and conceptually coming close to the source imagery in order to comingle the aesthetics of the digital and the painterly, so that they are fused and disjointed simultaneously, and therefore the ways in which we look at the world are seen to be a set of repeating patterns, distant and different over time. The landscapes which Martin paints have within them (as their collective title suggests) a sense of impending doom, of a catastrophe unfolding in which the capacity to digitally imagine such a landscape is linked to and is part of the cataclysm, and Martin’s work ask the question of whether the painterly, as a medium, is aesthetically restorative or whether it is simply a previous step in the human visual imaginary. Like much of Foreword, Martin’s work is open to thinking about the nature of the visual in synchronic and diachronic complexity and wondering how and whether the digital has changed the way we see.

The curation of Foreword explores a wide range of ways in which the contemporary image is altered and reimagined–by artists, by algorithms and programmes, by culture, by history, by ideology and by assumptions. Mishka Henner’s impishly serious work, Words and Pictures, is interested in letting pre-digital art forms clash with generative processes. The visual element of Henner’s piece here creates a series of playful images which allude to—but are never quite in alignment with—tropes of western and non-western art history, as if we are seeing a twisting of convention and futurity unfold (automobiles, for example, feature in pseudo-cave art or in Bosch-like landscapes). But Henner’s practice is nuanced by a satiric and often biting analysis of how the language and conceptualisation of contemporary art (and particularly photography) feed off and depend on a rhetorical emptiness or self-referentiality. His business cards, available here on a portentously minimalist stand, include his name and the text ‘mid-career artist’ (with no other details), while the wall text, which might have explained the work, is the standard Lorem ipsum placeholder text. And while there is always the potential for indulgence in parodic works, Henner avoids this by the energy and joy of his playfulness and the seriousness of the questions he asks about what the future role of photography might be.

Butler, Martin and Henner diversely raise the question of what happens to the past image in the present, and they do that partly by overlaying one on the other. The result is a query about the continuities of the image as a category—how the past of the image relates to the present. Works by other artists in Foreword strive to take the same dynamic into a framework in which the form of the image is present- and future-tense oriented, and in which the gamification of optics becomes a presiding and dominant means of knowing the world. Bassam Issa Al-Sabah and Jennifer Mehigan’s Uncensored Lilac is a visually rich piece which creates a series of fantastical visuals and aurally hypnotic reflections on a future, altered Ireland. A swirl of the mythic and poetic, filtered through a hypnotic script and woozy visuals, Uncensored Lilac shares with many works here a sense of a dread future which is not under human control but in which the ways things look will have political importance. The plaintive tone of much of the narration, on the edge of sense but speaking from within an alien epistemology, makes the piece both a lament for the present and an anxiety about the future, as if the ‘game’, the technology which allows speech here, is now playing by rules which it has invented for itself. Meanwhile, Dominic Hawgood’s Vestige Node is at the edges of AI-generated work that is visually recognisable as human-centred. The ‘image’ in Vestige Node is possibly of a complex microscopic entity, bacterial perhaps, but with no actual sense of scale or perspective on its being. On the reverse of the free-hanging image is a silvery, pockmarked substance which may or may not be related to the organism depicted on the reverse, as evidence of its life cycle or its capacity to damage. The result is as unsettling as Uncensored Lilac in its sense of computer code working with an entropic energy against the pre-digital conception of self and world.

Gaming technology, along with generative AI, continually raises a range of possible losses of human agency (and creativity), and this is, obviously, a common feature of recent discussions of and discourses around AI. To some extent, this returns us to the origins of photography as an art of mechanical reproduction and as an industrial and chemical process, and to the worries expressed in the nineteenth century about photography meaning the death of the artist. Photography’s indexicality and reproducibility were a challenge to this ideal of the romantic-artistic self, partly because it highlighted the proximity of repetitive visual cliché to notions of singular genius. If photography was always able to prick the bubble of the unrepeatability of brilliance, it has continued to do so exponentially as the photographic image has multiplied exponentially in the digital era. There is something of this consideration, beautifully and humanely imagined, in Penelope Umbrico’s Sunset Portraits from Flickr Sunsets. Umbrico’s vast work is a collection of images taken from Flickr of people, hopefully and with joy, posting a sunset image in which they or their loved ones appear. In these images, the same patterns, colours and sentiments are repeated over and over—the orange sun, the sea, the reflection of the last of the day’s light on the waves, the person/people in the image necessarily largely silhouetted because the sun is behind them. The images are clearly an attempt to record the fact of presence and the sense that the natural world and the turning of the earth is a wonder. They also speak of a desire to record and have evidence of the mere fact of existence and of a yearning for profundity. And yet they are, clearly, far from unique. They are the same sentiment, often (technically speaking) badly rendered, again and again. The non-identity of the individuals here, and their failure to be remarkable, might seem like a tragedy, but the overall effect of Umbrico’s piece is of collective light and a desire for meaning, and, indeed, of something visually spectacular, making the images, together, more than their individual parts.

Flickr seems, now, like a relatively naïve and benign form of social media in comparison to more recently devised torrents of information and opinion, urged on by ideological change in the western world, in which the image and the word are indistinguishable from the politics and the corporations which produce the platforms they flow on. Ana Zibelnoik and Jakob Ganslmeier’s Bereitschaft charts, through a musical-visual medley, the kinds of images and messages which produce a very particular way of thinking about masculinity on contemporary social media. Their work is a dissection of how ideas, such as Jordan Peterson’s, become embedded in the minds of young men who are in search of fixed and certain meanings. Zibelnoik and Ganslmeier take us through a building crescendo of images of masculine frailty that is the foundation of the move towards assertion. While Bereitschaft has the general meaning in German of a willingness to act, its specific visual reference here is to Arno Breker’s sculpture of the same name (1939) which has become a focal point for contemporary hyper-masculine ideology (and neo-fascist ideas—Breker was deeply implicated in Nazi culture), and so Bereitschaft thinks through the recurrence of the visual as a support to and focal point for right-wing thought, as well as being an examination of the role of social media.

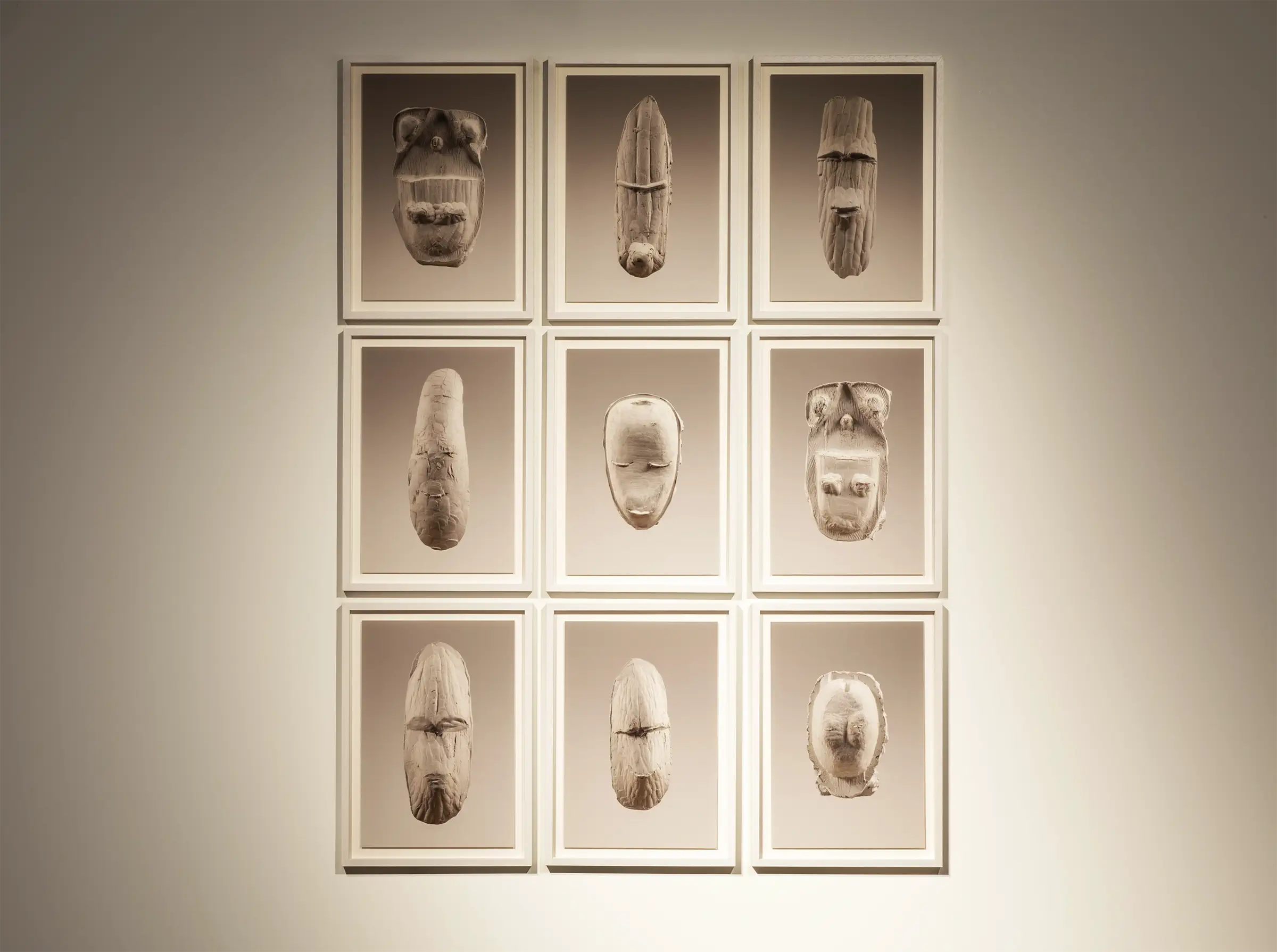

Three sets of works in Foreword feature artists who consider how the non-Western world is produced by or against contemporary image networks. House of Memory by Basil Al-Rawi is a tender use of virtual reality to invent (or re-invent) a version of Iraq from photographs in the Iraq Photo Archive. It is an intimate and domestic space—utopian, everyday and imagined—which creates a visual counternarrative to how Iraq is more generally understood (especially in the West) while pulling on the resources of a diaspora and generating an alternative reality (of what is a complex and rich historical culture) to be preserved and explored. Anna Ehrenstein’s Melody For A Harem Girl By The Sea playfully interlaces lenticular images of Muslim women, which are stereotypical, with others that contradict those stereotypes. Whilst Anna Safiatou Touré’s multimedia work Gamanké Museum (involving immersive gaming and photographic display) derives itself from a living and historical culture in sub-Saharan Africa, contesting how it is rendered as a tourist experience, which in turn generates its own material culture.

Foreword presents a range of artists working at the edges of the photographic image, where the digital, in all its networked and algorithmic forms, entangles and reworks the photograph/image. Yet photography in its ‘traditional’ forms persists, and Foreword has space for photographers thinking from inside the boundaries of the photograph as it has come to exist on a gallery wall. Abigail O’Brien’s Justice – Never Enough displays the hygienically technophile factory in which Aston Martin cars are made—the cars in question fetish objects of high-end masculine consumerism, with quietly added text drawing attention to the braggadocio which is inherent in the brand’s self-image (via reference to James Bond’s association with Aston Martin).

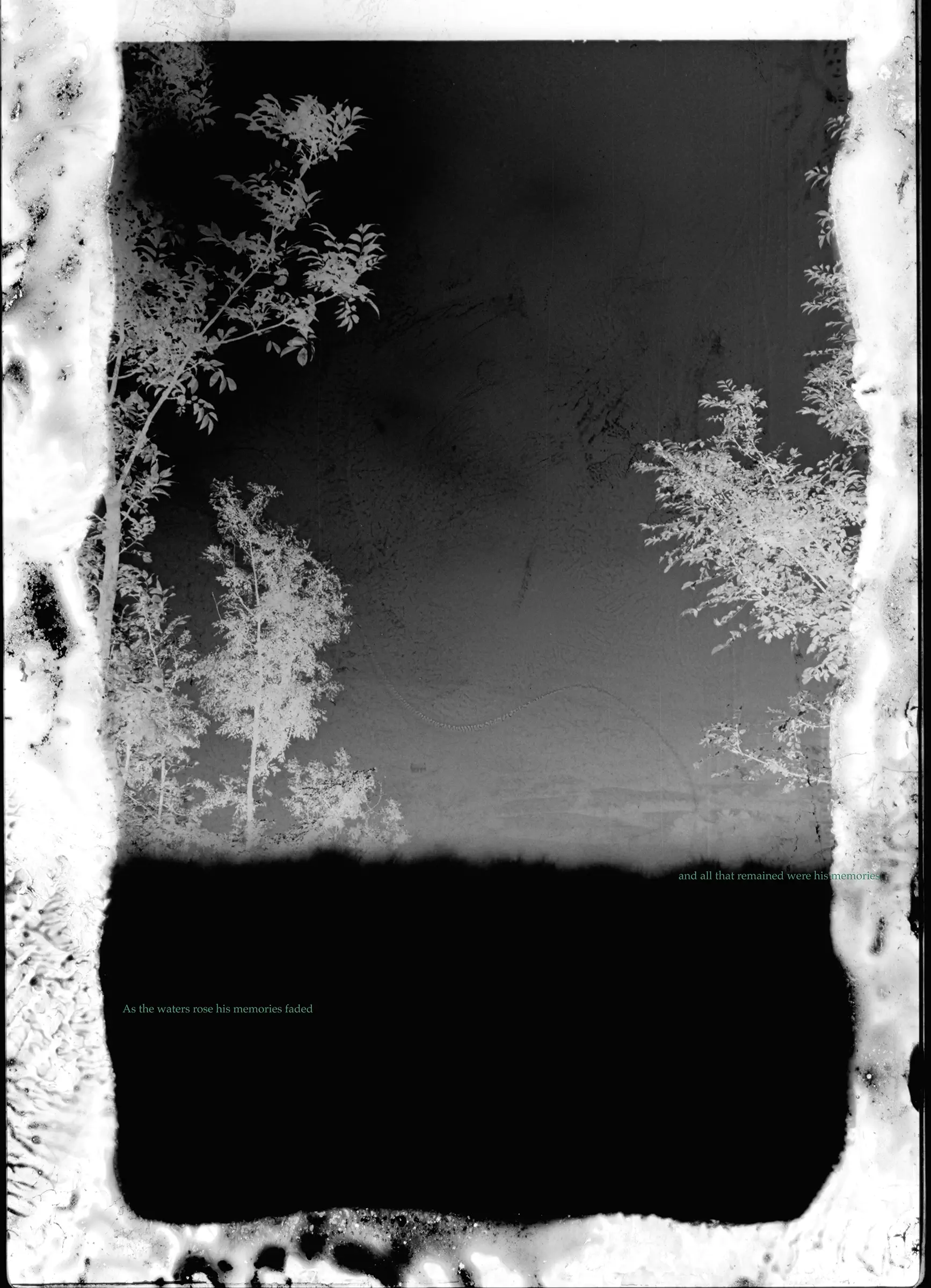

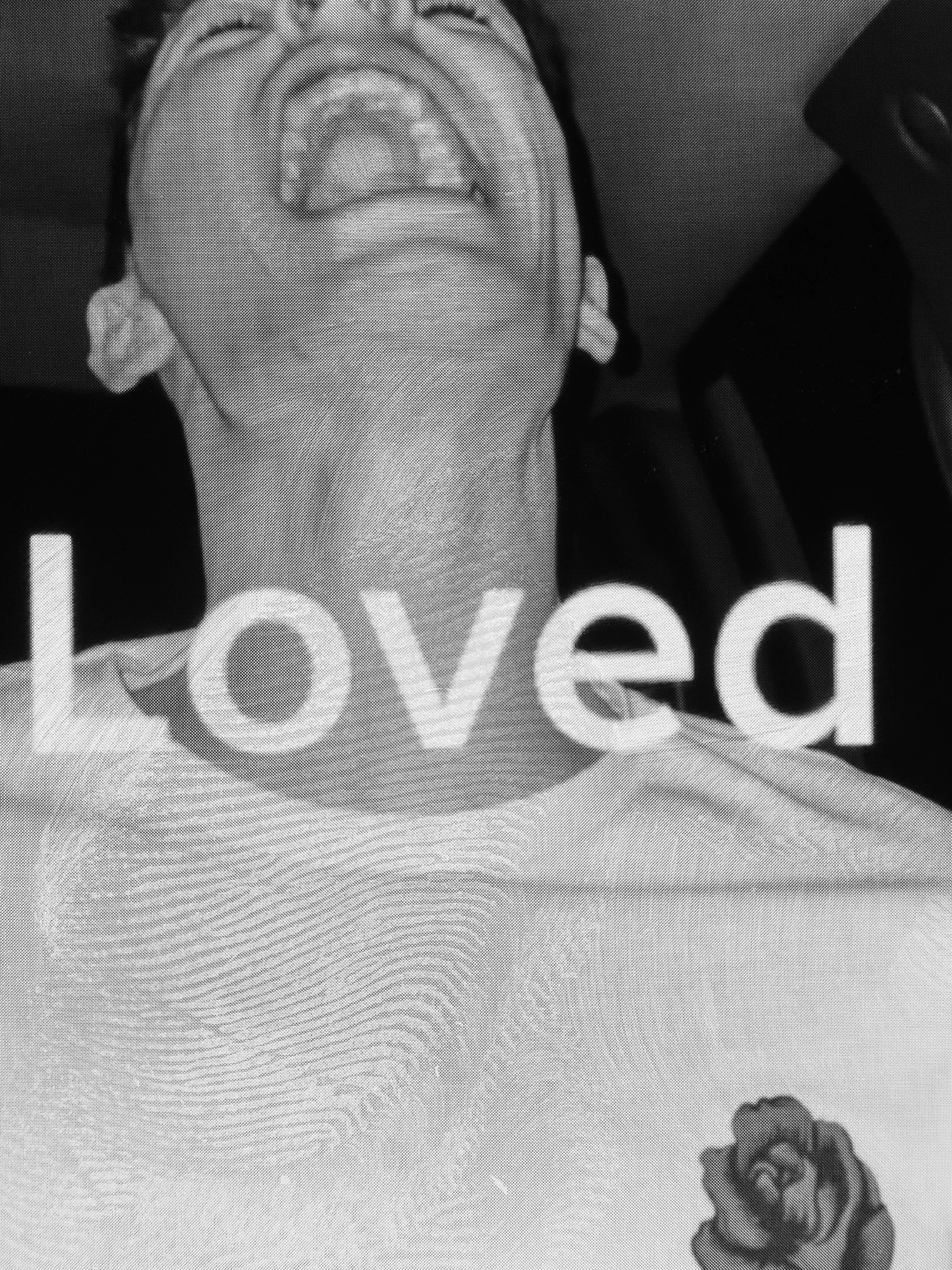

Eamonn Doyle’s new work AS IF also involves text and photography, along with an abstraction of shape and texture, which seeks to allow something to emerge from and blend with the photographs at the centre of the work. And this sense of erasure or intervention in the photographic image is also present in David Farrell’s work. Lugo Lament arises from the damage done to Farrell’s extensive archive in the floods in Italy in 2023, with the marks of the water, and what are presumably Farrell’s attempts to reconstruct his archive, visible on the prints.

At the physical centre of Foreword is Alex Prager’s Run, a film in which a large silver ball pushed along a town street by business people turns into a pinball comically and surreally knocking over and flattening pedestrians, and in which a heroine avoids tragedy and has the redemptive power to return things to equilibrium. In its hyper-real parody of technicolour and the post-war Hollywood era, Run shares many of the features of the work featured in Foreword—a belief in the power of the image, and an understanding that in order for art to harness that power, it must immerse itself in the most mediated versions of the popular image to recuperate human and artistic agency. More abstractly, Jean Curran’s Spring: Begin Again does something similar—a large-scale assemblage piece in vivid block colours, close to a painting in form, and something like a distillation of the techniques in Curran’s best-known work using film stills, and thus looking back, like Prager, to see what can be recuperated from pioneering moving image forms.

Foreword, in its multiplicity and ambition, signals exactly what its title indicates: it is a prelude, and one akeen to Dewdney’s proposed forgetting and reimaging the visual in new ways. It is a singularly hopeful sign of what is to come in the International Centre for the Image —a place for the image, in all its potential and all its contemporary modes, to be made, to be seen, to be comprehended.

.webp)

.webp)