Almost All the Flowers in My Mother’s Garden

“The habit, the interest in cultivating plants that could not be eaten, spread, and so did the ground surrendered to it. Exchanging, sharing a cutting here, a root there, a bulb or two became so frenetic a land grab, husbands complained of neglect and the disappointingly small harvest of radishes, or the too short rows of collard, beets. The women kept on with their vegetable gardens in back, but little by little its produce became like flowers―driven by desire, not necessity. Iris, phlox, rose and peonies took up more and more time, quiet boasting and so much space new butterflies journeyed miles to brood in Ruby”.1 — Toni Morrison, Paradise

When heat and drought tortured many parts of Europe this past summer, I reflected on how privileged it is to have a flower garden. Not only do they need water and nutrients, but flowers also require significant care and attention, and the leisure time that comes with these demands. Then there is the privilege of tending to and cultivating a garden that produces no food, only aesthetic beauty. One can simply look at and love the flowers. Perhaps more than anything else.

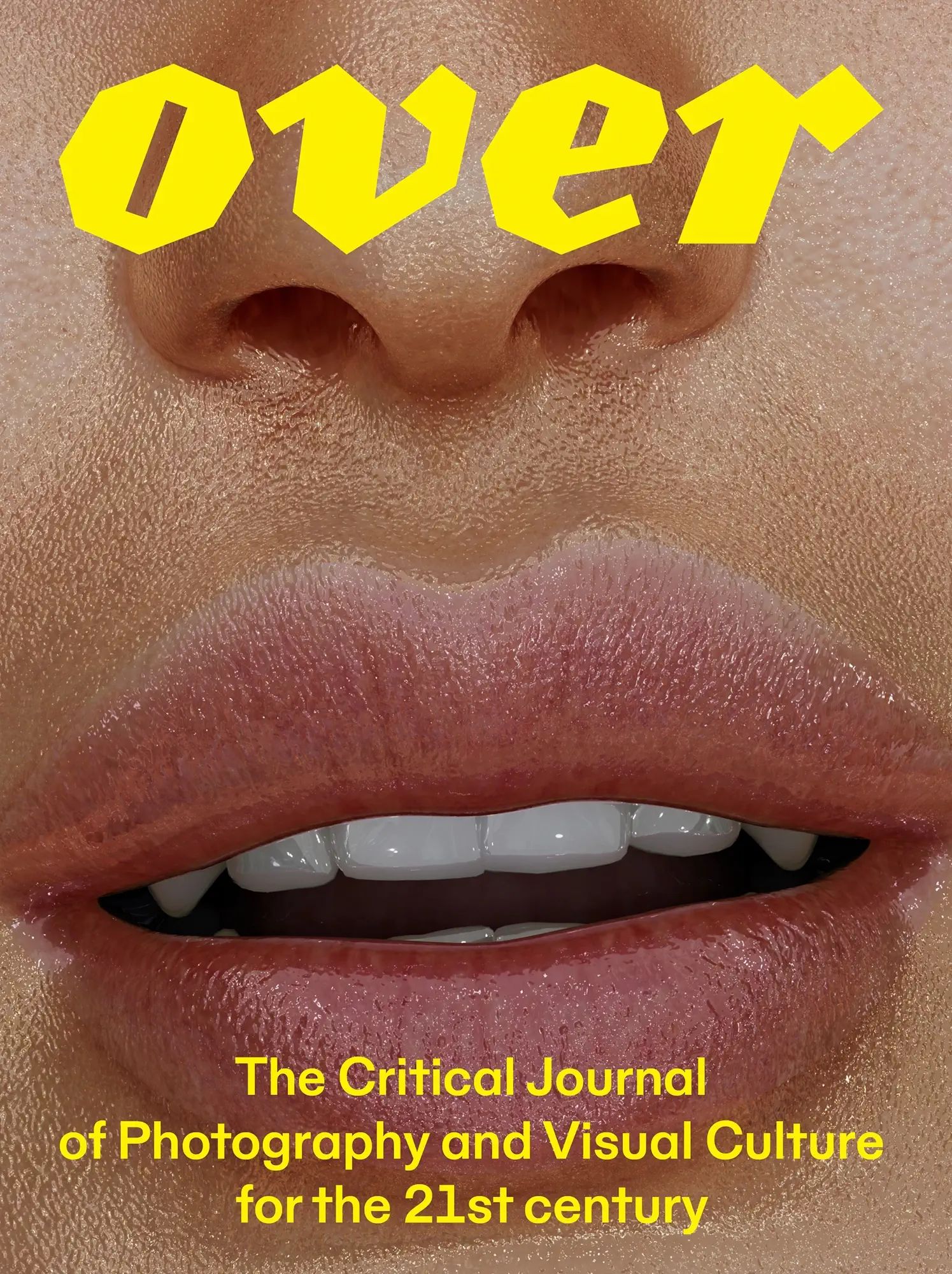

Love and care are also the themes of Hilla Kurki’s Almost All the Flowers in My Mother's Garden (2022). The book contains more than one hundred photos of flowers planted, grown, and cared for by Kurki’s mother, with the artist displaying them as beautiful, individual living creatures. The pages of the book are printed with the riso-printing technique, whereby the flowers organically merge into part of the soft paper. The result is small and light, convenient to carry, a nice-to-touch object that feels like both a field guide to plants and a life survival manual.

Interspersed with photographs of flowers, the book contains continuous short texts by more than ten women writers―including Kurki, The artist invited friends and acquaintances to share memories of their mothers, which are often everyday observations, alternating experiences of longing and rejection. Memories of care, or lack thereof. The writers’ memories are both sensual and social. Once engrossed in the text, the reader’s own childhood memories begin mixing with those of the writers.

Kurki asked the writers to begin each of their recollections with “I remember”. In doing so, and as a source of inspiration, Kurki refers to I remember (1970) by author and artist Joe Brainard. In his work, Brainard creates a strong emotional picture of his childhood and life in the United States during the 1940s–70s. The

memories in both books stress that the stories we tell―to both ourselves and others―are not necessarily factual. The memoirist is a character in their own story. Sharing memories with others is only a reflection. Intentions may be good, but are not commensurate with the truth. Memories are indeed not the truth; they change every time they are told and retold. The soft print of Kurki’s book and the subtle blurriness of the photographs seem a nod to the inaccuracy and loss of memories.

A few years ago, Kurki noticed she was jealous of her mother’s flower garden. The care and touch the garden received seemed unfamiliar and strange to Kurki. She began to see the flowers as creatures competing for her mother’s attention. Kurki’s reaction gave her pause to consider her relationship with her mother more deeply, and she consciously began recalling details from childhood. At first, Kurki felt guilty about what she remembered―even if she believed her mother had tried her best, painful memories came to the surface.

Is the welfare state a woman’s best friend?

“The welfare state is a woman’s best friend”, or so it has often been said. The Nordic welfare state was created in the reconstruction period following the World Wars. During the Second World War, Finnish women worked in factories, schools, and hospitals and took care of farms. After the war, they did not return home but rather stayed in the workplace. In the 1970s, the first parental leave system was created in Finland and public education in early childhood was regulated by law. The welfare state not only freed―but also obliged―women to work, study, and run a domestic life.

In the 1980s, researcher Helga Hernes called the Nordic countries women-friendly welfare states. Hernes defined such a state as one that does not force women to make more difficult choices than men―in relation to work and family, for example―or allow gender-based discrimination. Woman-friendly social policy includes extensive public services and practices that facilitate combining work and family, promoting women’s participation in the labour market. However, policies intended as woman-friendly can also have unintended consequences. Due to gender-segregated labour markets and family leave taken mostly by women, it would be more difficult for Nordic women to reach leadership positions and high salaries. This mechanism is known as the paradox of the woman-friendly welfare state.

The role of a woman and mother living in the Nordic welfare state has steadily been dismantled in photographic art since it was first created. The home, daily life, gardens, and flowers have long been the domain of female artists. The 1970s feminist slogan “the personal is political” sought to highlight women’s lives in the domestic and private sphere, and thereby reveal structural gender inequality along with unequal income distribution in the welfare society. Especially in feminist art, attention was paid to unwaged work and care outside the public sphere, as the naming of daily life and care labour produced information about entrenched social structures. Power dynamics were hidden in everyday things and major structural problems were often located in phenomena around the home and in experiences considered personal. In the early 1980s, women photographers broke away from the documentary tradition. Although female photographers were not a united group, many shared the questions of subjectivity related to photographing everyday life or presenting one’s personal and family history.

At the end of the 1990s and in the beginning of the 2000s came the so-called ‘girl boom’. The sociological study of girl cultures became active and several exhibitions in the visual arts dealt with girlhood. In the Nordic literature of the time, writers dealt with personal and difficult topics in the lives of young women: the presentation of the body and being seen, violence, and the right of a woman to self-ownership. But at the same time, girlhood was seen as a feminine project. Girlhood was accused of the very qualities that were often typical of it: superficiality, lightness, and a lack of awareness. Paradoxically, at the beginning of the 21st century, girlhood was “cured” by leaving it behind and growing up to become an aware, responsible woman and mother, following the model of the previous generation.

“My mother takes care of her garden so intensely that she wakes up in the middle of the night to take the radiator into the greenhouse if there is a fear that the plants will freeze”.

Hilla Kurki’s Almost All the Flowers in My Mother's Garden can be seen in the same continuum; works of art that reconstruct the gendered and generational structure of the Nordic welfare society. The memoirists are connected by their identity as women and artists. All are daughters whose mothers were born in the post-war era. Rather than the memory of one daughter alone, the text becomes rich in detail, a harmony of voices, a generational experience by and about young women and their mothers. This experience is not about being daughters, but rather the relationship with their mothers. The mothers in the book represent a peculiar generation, one in which the model woman feels alien today. The mother appears as a confusing woman whose world the adult daughter does not share. When thinking about her mother, the daughter tells herself: “I will not become like you”.

A wide range of emotions lies at the heart of Almost All the Flowers in My Mother’s Garden, stemming from social concepts related to femininity, motherhood, artistic identity, and class. Kurki has previously worked with these questions, with past works including the mourning after the death of her sister, in which she relied on her mother’s family tradition of carpet weaving. Kurki has said that she does not have another language to talk about art―or feelings―with her mother. Kurki’s mother comes from a working-class family, and Kurki is the first woman on that side to earn a university degree. Despite training as an artist, Kurki was also educated in nursing and still works in child protection.

“What is the most important thing in life?” Hilla Kurki was asked during her studies. “Mercy”, she replied. At the time, mercy meant that Kurki allowed herself to use the tragedy of her sister’s death to create photographs. In Almost All the Flowers in My Mother's Garden, important things in life and mercy are still present but in another way.

I’m drawn to the idea of flowers and flower gardens as a necessity to meet the human need for beauty and care. Hilla Kurki’s mother’s flower garden is essential for her. Maybe it even keeps her alive? Kurki is searching for a common language with her mother, with whom she has not felt connected before. The flowers loved by Kurki’s mother turn into her art; the flowers have acted as a medium for connection between mother and daughter. The book asks the mother to see what her daughter does. To understand how her generation thinks. Mercy is not a common understanding, but a search for connection over the generational gap. Both daughter and mother can be proud of each other.

Image above by Hilla Kurki

1 Morrison, T. (2010). Paradise. Penguin Random House.