After All: PHotoESPAÑA 2025

OVER Journal visited PHotoESPAÑA at the start of its season. In Madrid, the festival is divided into two main strands: an Official Section in prestigious museums and institutions and a Festival Off in commercial galleries. Additionally, there is a new open‑space circuit. Even though each edition has its dynamics, most apparent is the overall focus on past achievements and in those revivals, special attention is given to Spanish artists of yesteryears.

PHotoESPAÑA is a major collective project consisting of photography exhibitions divided over approximately 130 private and public institutions throughout the country, but particularly concentrated in the capital city. Showcasing the reach of photography while also promoting the many collaborations between public and (semi-)private institutions within the cultural sector in Spain seems to have always been the main objective of the event.2 Seen in that way, when the manifestation is so comprehensive and taking place at so many locations at once, communicating an overarching thematic framework in an articulated manner is not so easy.

The curatorial aim for PHotoESPAÑA 2025 was nevertheless “to spotlight the work of photographers / visual artists who have chosen to confront reality critically”. While this is in itself an admirable ambition, hinting at a special attention to the longstanding tradition of ‘concerned photography’, it also contains the risk of remaining a bit of a platitude. The hodgepodge of exhibitions at least doesn’t result in a firm expression of anything specific enough to have this year’s edition of the festival clearly distinguished from previous ones. Moreover, if deeming the fostering of an ecosystem that encourages the innovative and imaginative new approaches to the medium as also significant, a visitor with a ‘passepartout’ will find that many, if not most of the venues present a rather limited understanding of what could fit this year’s motto: Después de Todo or 'After All’.3

That the organisers of PHotoESPAÑA are not completely blind to the talents of today speaks from the prominent stage for the American artist Ayana V. Jackson (b. 1977), who is best known for mapping ethical considerations and relationships between herself as the photographer and as the subject, exploring themes around race, gender and reproduction she confronts the viewer with our historical tropes and social stereotypes. In her immersive and feminist approach to portraiture, Jackson often casts herself in the role of historical figures to help guide their narrative and directly access the impact of photography and its relationship to the human body.4

Nosce Te Ipsum (‘Know Thyself’), on show at the National Museum of Anthropology in Madrid, deals with a tracing of the Afro and Afromestizo presences in the Spanish state collections and with that Jackson offers a direct dialogue with the hosting museum concerning their evolving and progressively challenging position in the process of (de)colonisation — a hot topic that museums find themselves juggling with nowadays.

Elsewhere in the city, MAPFRE5 showcases Spanish artist Jose Guerrero (b.1979) alongside Colombian artist Felipe Romero Beltran (b.1992), two contemporaries whose work has a focus on landscapes in a manner that goes far beyond mere representation. Guerrero’s work is systematically organised in series about iconographically and historically significant places, such as London’s Thames, the marble mines of Carrara (Italy), and iconic Spanish regions like Sierra Nevada and La Mancha.

“Through a significant use of light, colour and atmosphere, his images appeal to the cultural and emotional connotations of these spaces, leading the viewer to construct, through a poetic and meaning-filled gaze, their own narrative of what they are witnessing,” reads the introduction on the wall. Guerrero’s work explores the landscape as an entity intertwining history, culture, and the collective imagination.6 Even when his (mostly large-scale) prints exclude the presence of people, the landscapes depicted trigger a contemplation about ourselves and our relationship with these environments.

Felipe Romero Beltrán is specifically concerned with territories that have been or are the scenes of tension in the context of (im)migration. The exhibition “Bravo” is conceived as a photographic essay in fifty-two images and a video that together explore the area where the Río Bravo — which forms the border between Mexico and the United States — changes its name to the Rio Grande. It is there that people from Colombia, Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala are coming together.

What we see are mainly empty interiors, walls and surfaces marked by textures and colours, as well as portraits of individuals with whom the artist has crossed paths during his travels in the region. Beltrán’s images reflect the looming tensions between this architecture, those people, and the landscapes they are crossing, live near, or are affected by in one way or another due to their migration. Furthermore, his commitment to the complex, evolving sense of self that emerges from living near (or with) national boundaries — whether physical, social, or symbolic — also brings to light an interesting and delicate distinction between the photographer as passive observer versus the active participant.

Shedding light on how the camera can become a tool for contemplation on our surroundings (Guerrero), on explorations of our physical and ethical borders (Romero), or on forcing us to rethink biases (Jackson), these are all subthemes worthy of being highlighted. Nevertheless, the overall majority of the PHotoESPAÑA productions, initiated by La Fábrica and by the several partner institutions, are mostly stand-alone confirmations of already celebrated achievements.

Lourdes Grobet once recorded the “Peasant and Indigenous Theatre Laboratory” (LTCI), a folk-rooted theatre in Mexico, organising collective performances directed by the playwright Alicia Martinez Medrano.7 At PHE, a sample of the 25,000 negatives arriving from that body of work can be seen at the Fundación Casa de México En Espaňa, where Grobet’s apex is on show alongside Graciele Iturbide (b.1942), another key figure of Mexican photography, and El Camino Al Tepeyac (‘The Road To Tepeyac’), a widely exhibited work of the relatively young, contemporary artist Alinka Echeverria (b. 1981). This bringing together of three Mexican female photographers can be interesting in itself, yet it also indicates that the hosting institution has an agenda not necessarily colliding with the overarching theme of the festival.

Nicholas Nixon’s longitudinal “The Brown Sisters” is also on the walls at MAPFRE; Duane Michals’ 20th-century conceptual work can be seen at Fundación Canal; the pioneering achievements of British Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879) are on show at the Royal Theatre in Madrid. Furthermore, especially focusing on Chile this year, PHotoESPAÑA stages the historically significant achievements of Carlota Eugenia "Lotty" Rosenfeld Villarreal (1943-2020), Julia Toro (b. 1933), Michael Mauney (b. 1937), and Martin Gusinde (1886-1969) — some who are Chilean by birth but all were once active in the country as photographers/visual artists.

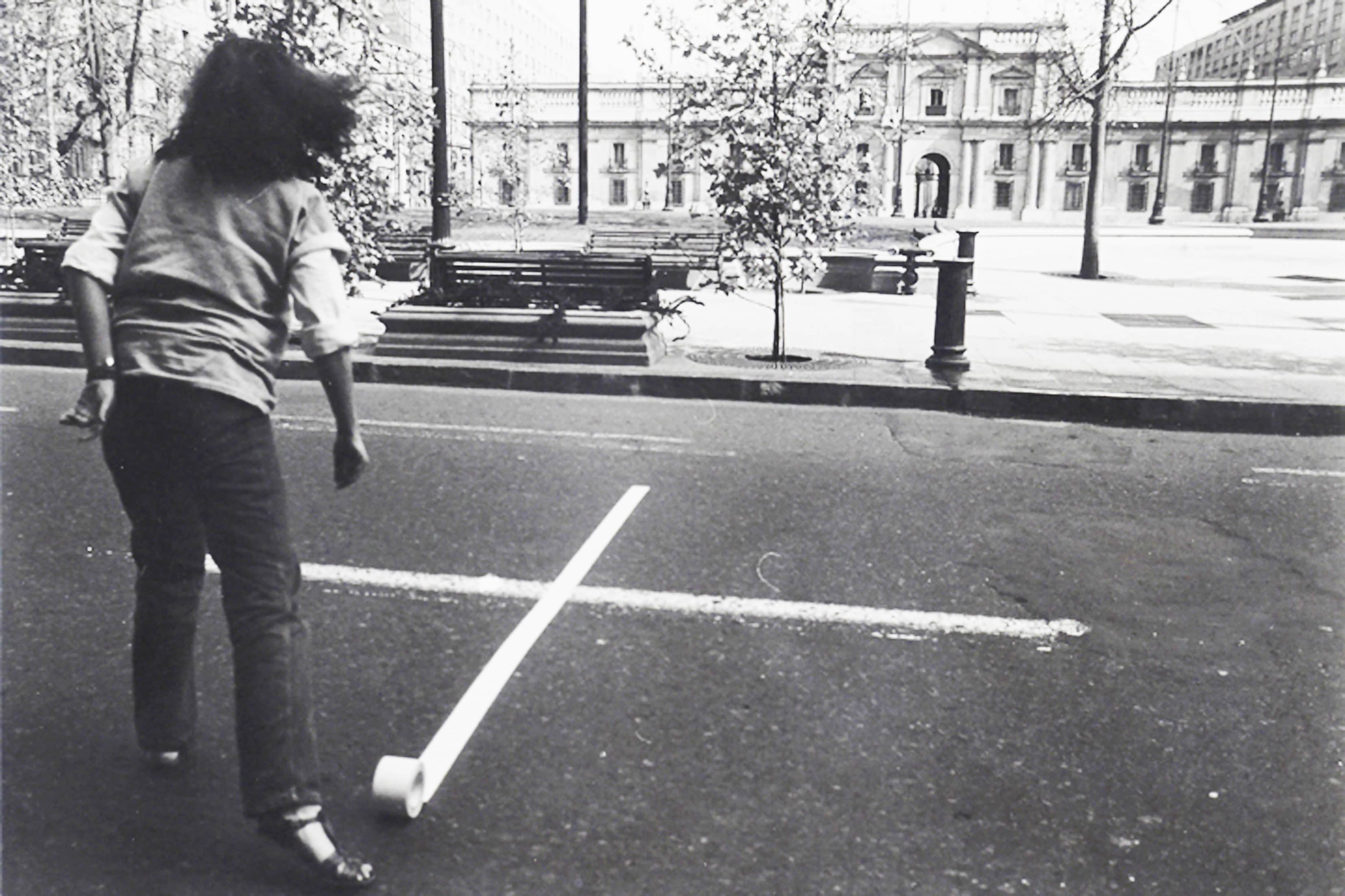

Lotty Rosenfeld, La Moneda, 1985. Courtesy to the artist and ACA

Lotty Rosenfeld was an interdisciplinary artist and a brave visual activist during the fearful Pinochet regime of the 1970s, and her work, rooted in resistance and civic participation, was characterised by provocative public art interventions. Elsewhere in the city, a selection of Julia Toro’s photography will be featured, spanning from the dictatorship era to the present day. PHotoESPAÑA’s commitment to Chilean photography will even extend to the autumn: from September 11th (a significant date for Chile too) the House of America in Madrid will host an overview of Michael Mauney (b. 1937, USA), who arrived in Santiago as a Life photographer to portray Salvador Allende.8

In the context of PHotoESPAÑA 2025, and its more general mission to push the humanistic scope and to stage previously underrepresented artists, the special focus on Chile certainly adds an important extra element to the main programme. However, when taking a more critical stance one could also come to wonder: were there really no curatorial ambitions to have these significant 20th century figures, and the themes that they touched on, connected with what concerns the Chilean lens-based art community today? Apparently not.

«Artistic voices from the past

may resonate too weakly

against present concerns.»

When Alberto Anaut9 came up with the idea of launching and international photography festival in Madrid, roughly thirty years ago, he set a very clear objective: to spotlight photography — the most contemporary medium of expression — and to give it the place it deserved in the art world; to initiate “an open project where creators and art professionals, cultural institutions, public administrators and companies with widely diverging missions can meet to promote photography.”10 Unfortunately, at least this time, the attention being given to the ‘heroes’ of photography somewhat overshadows the practice of today’s photographic communities — with a few contemporary (conceptual) photographers and the display of The Best Photography Books of The Year, acknowledging the domestic and international publishing industry, as anomalies.11

The selected ‘photobooks’, sampling the best of the crop of the past year and together making for a good reflection of what concerns photographers today, are to be found at a corridor before the entrance of a major overview of the American photographer Joel Meyerowitz, who in 1966 embarked on a year-long European road trip, visiting 10 countries, travelling 30,000km and taking about 25,000 pictures. Impressive as that is, and as pleasant as it is for the eye to relive this ‘road trip’ that helped Meyerowitz to shape his unique eye for street scenes, what does it all have to do with what is happening in Europe today?

Catalan artist Espe Pons (b. 1973) recently traced the places where the German philosopher Walter Benjamin (1892-1940) spent his last days, when he was fleeing from fascism.12 But showcasing it as a stand-alone exposé, and not juxtaposed with others delving into the meaning of a landscape in the context of (forced) migration, feels like a missed opportunity. Why, for instance, was Pons’ “Flucht”13 not put in context with the work of, let’s say, Lotty Rosenfeld, giving a firmer voice to the act of resistance? Or with Beltrán’s “Bravo”? Or with some other great projects of recent years touching on similar issues?

The many institutions involved in PHotoESPAÑA contribute to its extensive programme, delivering a wide selection of high-end humanistic photography, the social documentary practice that shaped a canon, but when critically reviewed, artistic voices from the past may resonate too weakly against present concerns.

The focus of this year’s edition of PHotoESPAÑA is clearly on looking back at highlights from the past. While it can be worthwhile to arrange call-backs to canonical works of internationally acclaimed artists, let’s be reminded of what Walter Benjamin once noted: the past is not a closed chapter in history, but a living force that continues to exert influence on the present.14 There is no lack of critical voices echoing from the many venues’ walls, be it that they mainly reflect 20th-century photography as created by artists who — often bravely — examined the medium's relationship to power, class, and the capitalist system.

For the sake of keeping it all relevant in context of current social and political affairs, why not have the older bodies of work activated in a curatorial bridging between eras? In a more balanced display, juxtaposed with the paradigm of today’s art-activism, and perhaps also more firmly connected with the current wave of Spanish (post-)photography? Unfortunately, the curators did not programme too much that makes for a coherent and overarching theme — be it as a faux-pas or for very practical reasons (because the institutions follow their own agendas). Yet, that aspect of connecting the dots seems to have become somewhat lost in the set-up of PHotoESPAÑA 2025.

1 Quoted from the curatorial introduction to the PHE catalogue.

2 PHotoESPAÑA was launched at a time when Spain was asserting its modern, and newly democratic, identity and integrating more fully into global cultural networks. The festival, at its inauguration, represented a conscious effort to legitimise photography as a serious artistic medium within Spain, and create a space for free, critical expression — something that had been heavily suppressed under Franco.

3 It has to be noted that Erik Vroons was in Madrid for a few days in the beginning of June and could only visit a limited number of all the exhibitions available.

4 https://marianeibrahim.com/artists/27-ayana-v.-jackson/

5 Fundación MAPFRE, a non-profit organisation founded in 1975 by the main insurance company in Spain, has a proven commitment to the current wave of photography by consistently giving space to early- and mid-career artists to present their work prominently in their white cube exhibition halls.

6 PHE catalogue, p.68

7 The LTCI was a revolutionary initiative: conceived as a space for collective theatrical creation with indigenous communities from southeastern Mexico, its primary goal was the documentation and preservation of oral traditions. Among the groups most actively involved in this theatrical creation—and in using it as a tool for expression and resistance—were members of the Chontal, Chol, Zoque, Maya, Mayo, and Náhuatl peoples. A selection of nearly seventy photographs from the project developed by Lourdes Grobet (Mexico City, Mexico, 1940–2022) around the LTCI can be visited through August 31 at Fundación Casa de México in Spain, located at Alberto Aguilera 20, Madrid.

8 On 11 September 1973, a group of military officers, led by General Augusto Pinochet, seized power in a coup, ending civilian rule.

9 https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alberto_Anaut

10 A statement recalled by Alberto Fesser, President of La Fábrica, in the foreword to this year’s PhotoEspaña catalogue.

11 Los Mejores Libros de Fotografía del Aňo, on show at the entrance of Fernán Gómez Centro Cultural De La Villa. Pl. de Colón, 4, Salamanca, 28001 Madrid, Spain. In its 28th edition this award will recognise the best publications published between March 1, 2024, and March 1, 2025 , in four categories: Investigation, Creation, Bibliophilia, and First Publication.

12 Centre Cultural-Llibreria Blanquerna, Madrid. Pons’ “Flucht” is also shortlisted for The Best Photography Books of The Year and exhibited elsewhere in Madrid.

13 Pons’ “Flucht” was published as a book (2024) and as such it's also part of the Book of the Year display at PHE