On Image, Origin and Representation

Floating Signifiers: Case studies on image, origin and representation, a new publication by Daan Paans, brings together several case studies that offer insight into the socio-technological ecology of things and phenomena as expressed in the visual culture of the past, the present, and the future. The book, published by The Eriskay Connection (2025), is built around the idea that transmute primal forms still quietly echo in today’s visual culture, showing how archetypes change yet continue to resonate.1

“Ancient human fingerprint suggests Neanderthals made art,” reads a BBC headline, summarising how Spanish scientists recently unearthed a rock assumed to resemble a face. The premise is that, approximately 40.000 years ago, one of the Neanderthals found the stone "which caught his attention because of its fissures” and he intentionally made his mark with an ochre [pigment] stain in the middle of the object.2 This assumed subhuman symbolic capacity touches on phenomena called ‘pareidolia’—the tendency to perceive meaningful patterns, like faces or shapes, in random or ambiguous visual or auditory stimuli.3 But it could also be stated that the Neanderthal, who intentionally marked a stone with red pigment to make it resemble a human face, unintentionally ignited a long-standing “meme”. 4

Some linguists argue that humans have already “memed” for centuries, a claim seemingly proven by Dutch artist Daan Paans, as he investigates proto icons that evolve and are then reinterpreted, again and again; regularities that occur in an ecology of representations and thus slightly alter over time while remaining recognisable as archetypical templates. What he is particularly intrigued by are recurring ideas and interpretations; potent symbols or concepts that don't have a fixed, universally agreed-upon meaning

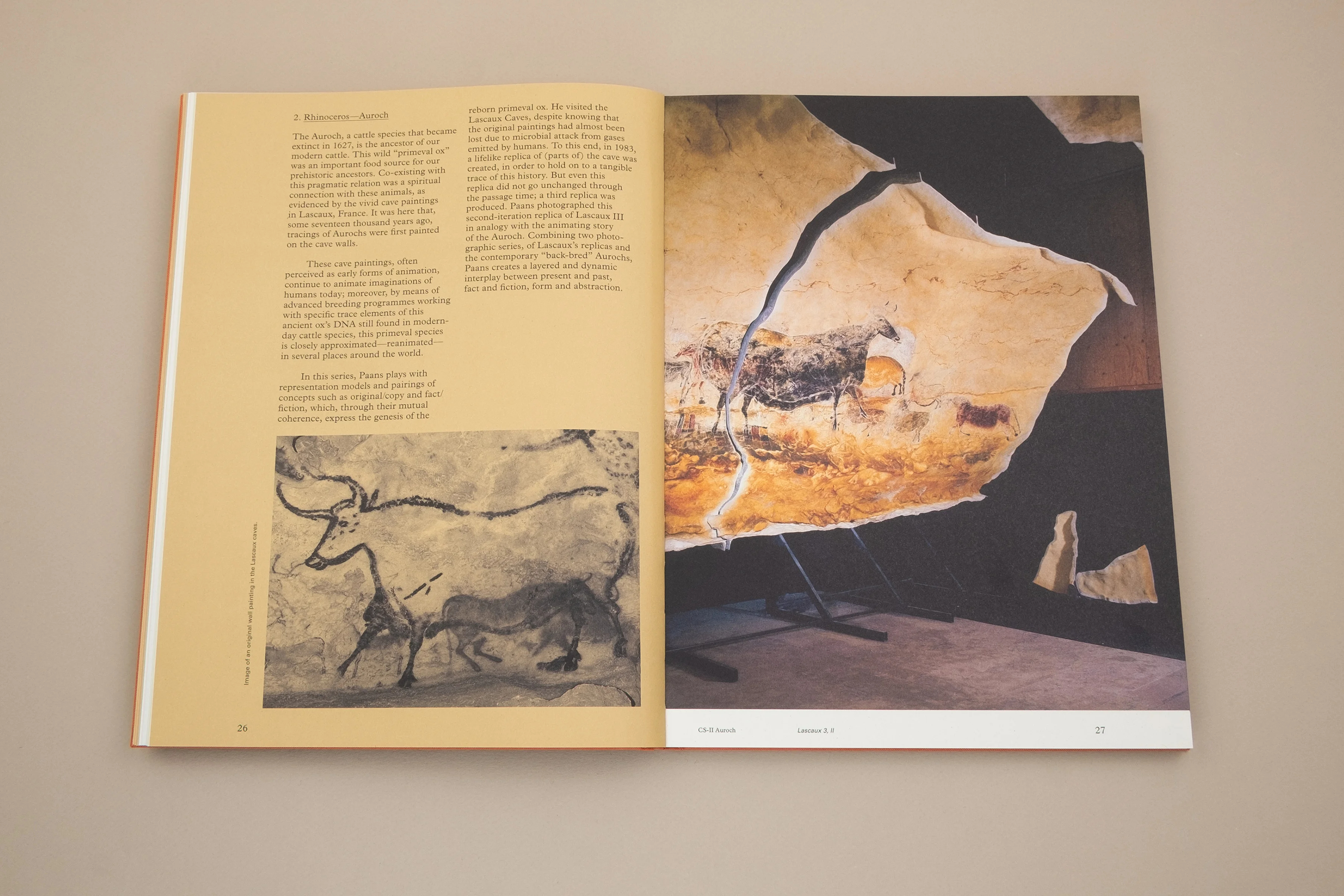

Over the course of a decade or so, operating in the rather broad (and ever-broadening) realm of visual culture, Paans explored how iconic images are produced, circulated, and interpreted within a particular cultural context. Focused on the leaps of thought that might entwine ancient views and modern ideas towards the possibility of cultural transformation, he analyses the genesis of a wide range of subjects. Such as: the extinct aurochs to the pre-human paradise, depiction of the rhinoceros, the oak tree, meteorites from sci-fi films, variations of the lion man, and the Golden Idol of Indiana Jones.5

Paans’ research methodology relies primarily on the photographic medium. Still, in developing his case studies, he expands his expression into multimedia installations, applying video, 3D renderings, sculptures, and documentary archive material—depending on the nature and meaning of the subject he explores. He also applied research methods from biological evolution and even made use of a supercomputer to predict the future form of cultural expressions.6 Here follows a few descriptions of Paans’ case studies, but first, something about the essence of “empty signifiers”:

Fredric Jameson, in an essay touching on the critical rethinking of high culture and mass culture as a strict dichotomy,7 famously suggests that the shark in the blockbuster film sequence Jaws is an “empty signifier”— a linguistic sign, a label or slogan with no fixed and delimited meaning, which can therefore be interpreted in many ways. Not having a specific meaning itself, because it is susceptible to multiple and even contradictory interpretations, it then functions primarily as a vehicle for absorbing whatever viewers want to impose upon it.8

The shark in these movies is not just that, a shark, as how its “sharkness” is understood can shift depending on the context or the user.9 Such phenomena, whose meaning is not fixed and is subject to change and interpretation across different contexts and audiences, is what Paans patiently studies in his Floating Signifiers; processes of interpretive multiplicity that have developed throughout history, to make practical how our view of the world has been kneaded and formed.10

How do things come into being? And how does the past, or the social constructs of time and space, manifest itself in the present?

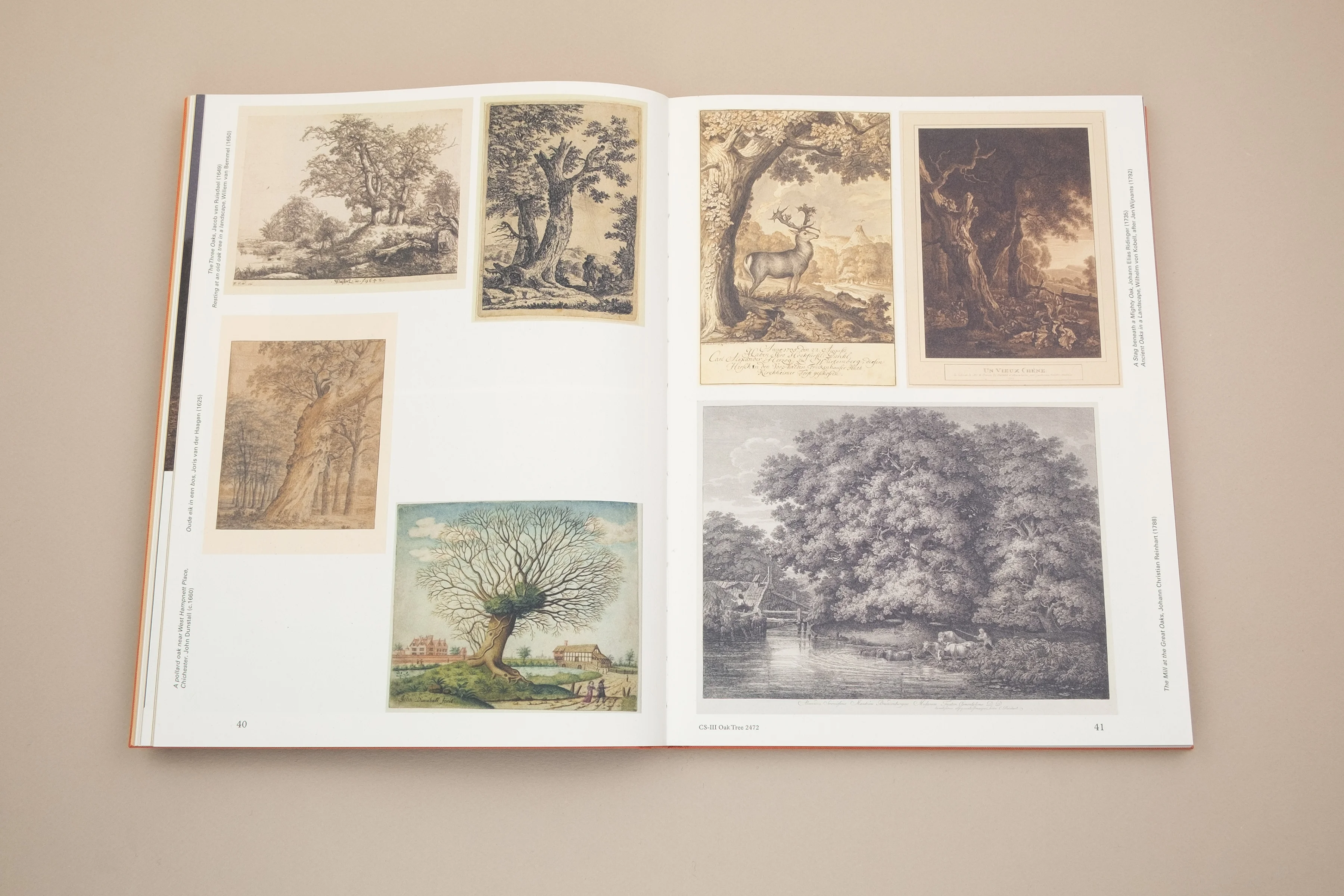

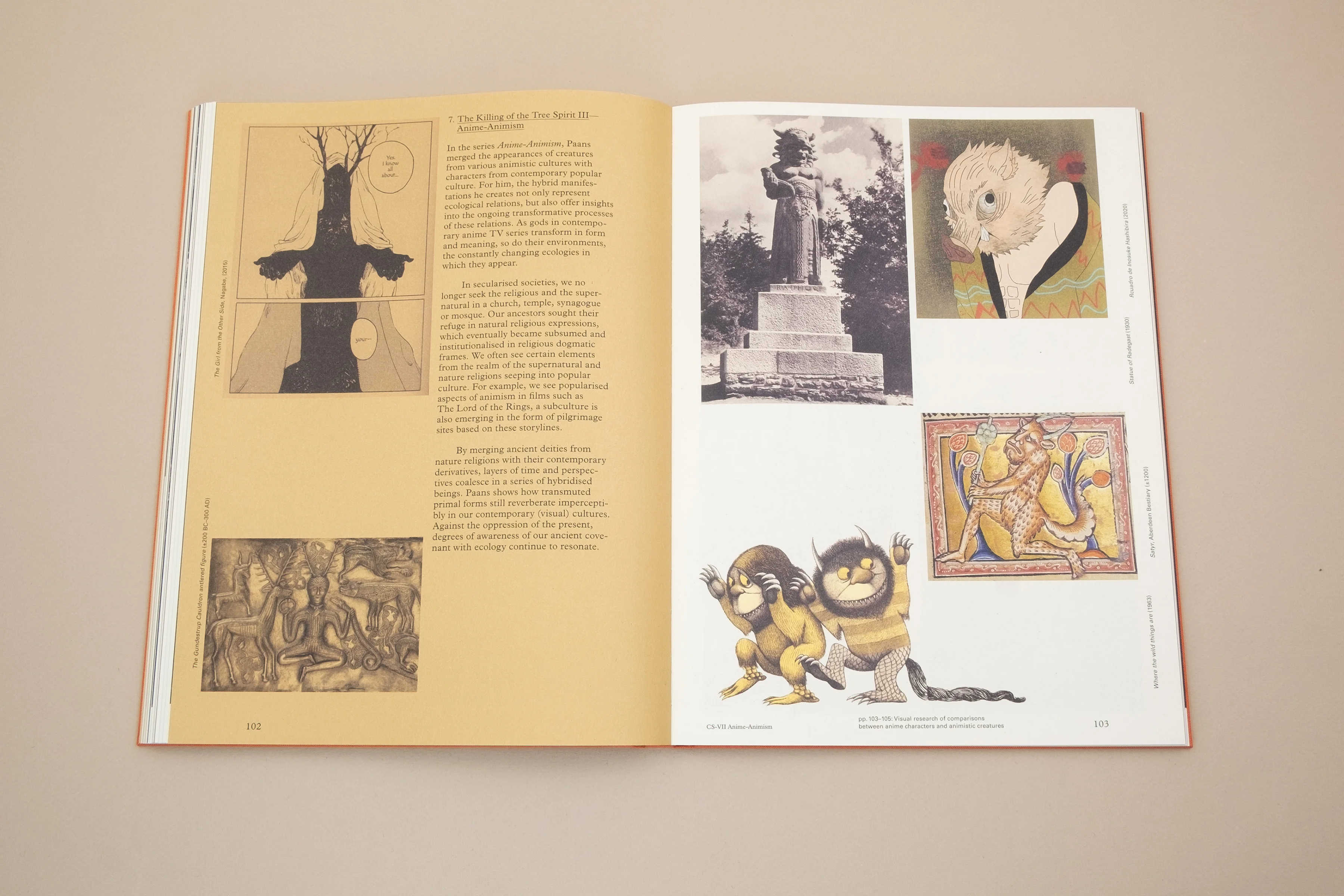

In another subchapter, The Killing of the Tree Spirit, Paans employed scientific software to render a speculative representation of an oak tree of the future, based on a dataset of dozens of oak-tree representations sampled from our cultural history. Meanwhile, fascinated by the connection between the imagery of Romanticism and today’s popular culture, he photographed the “Wodan Oaks of Wolfheze”: five winding short oaks that, because of their peculiar shape and estimated age (approx 400-600 years), gained a mysterious aura that inspired 19th-century Dutch painters, and these trees are now considered national natural heritage.

This speaks to Paans’ interest in how our perception of natural objects evolved and, in the case of the oaks, towards which versions of the iconic image they could eventually grow. He presents speculative possibilities surrounding the genealogies of iconic phenomena, as existing in nature (such as the oak tree, cherished across the world as a symbol of wisdom, strength and endurance), but also extends to predisposed entities reflecting the evolution of cultural artefacts.

Another case study deals with the Lion Human, evolving from the “proto” object produced ca. 3600 BC—an anthropomorphic figurine combining a human-like body with the head of a cave lion.11 The Lion Man—sculpted with great originality, virtuosity and technical skill from mammoth ivory — is the oldest known representation of a being that does not exist in physical form but symbolises ideas about the supernatural. It reminds me of the “chimeras”: mythical creatures often depicted as a hybrid of a lion, a goat, and a snake that have found representation in the arts, particularly in horror, fantasy, and science fiction. Mythical human-animal hybrids, as such, have evolved from ancient folklore to become an enduring staple in popular culture and reflect humanity's complex nature.12

This statement, as noted in the book, can be understood as a core motivation for Daan Paans’ artistic probes: “Science often finds a certain consensus about the original nature, meaning and function of such artefacts. What scientists have less control over, however, is the question of how various typological variations can arise across different cultures and zeitgeists. Due to reproduction processes, countless variations in representation come to the surface. This process is often difficult to unravel, yet every recognisable manifestation seems to trace back to a (series of) earlier version(s).”

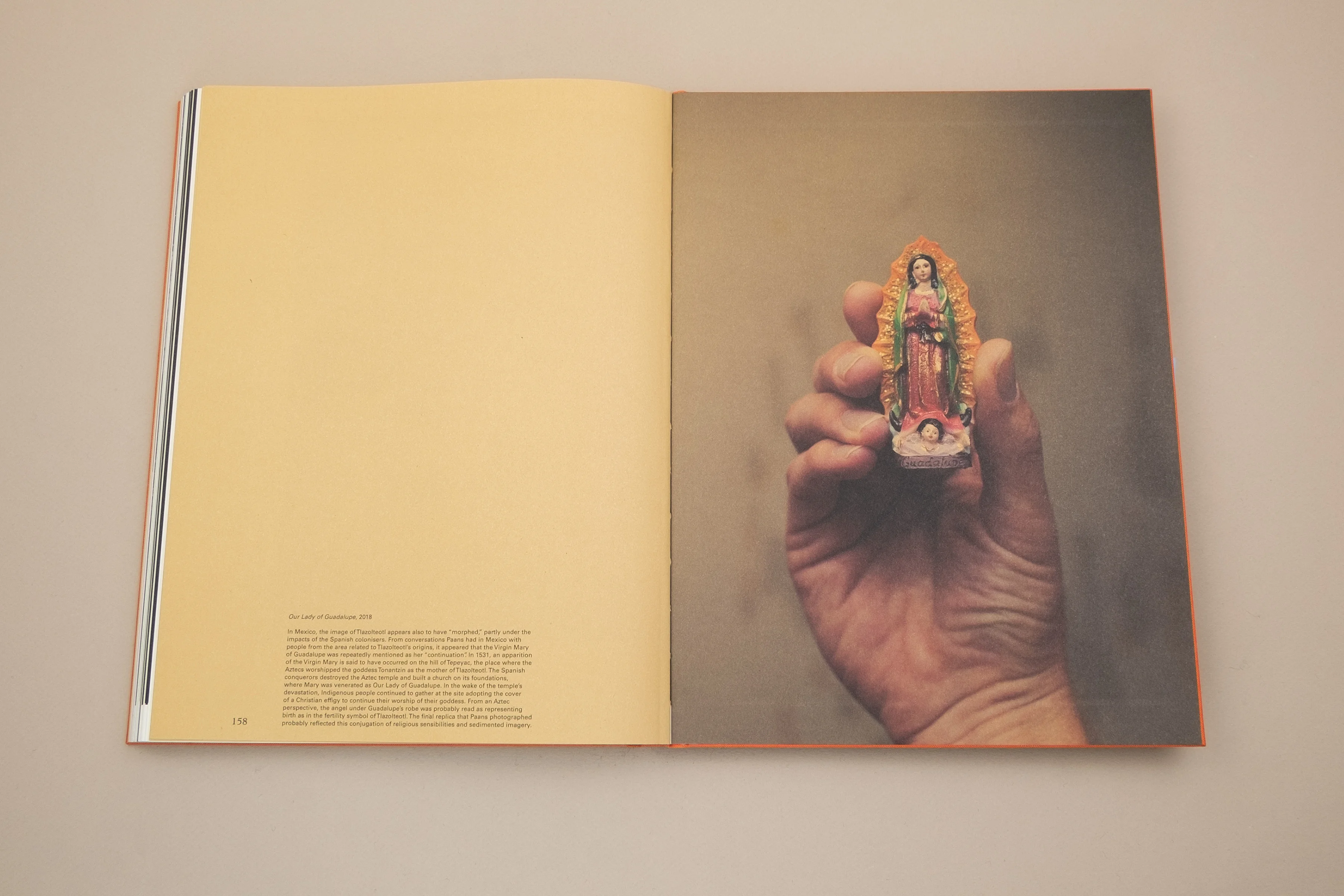

It all culminates in the Case Study IX, an exploration into the confusion that perfumes a pre-Columbian artifact held in the collection of the Dumbarton Oaks Museum in Washington; a birthing figure sculpture allegedly representing the Aztec goddess Tlazolteotl, likely produced in Europe or Asia in the nineteenth century— indicating that The Chachapoyan Fertility Idol, more commonly referred to as the Golden Idol, as appearing in the 1981 Indiana Jones movie, “transpires to likely be a fictional reinterpretation of something that might be in itself a piece of fiction”.13

First, the facts: In June 2021, to celebrate the 40th anniversary of Raiders of the Lost Ark, Disney released a limited-edition licensed prop replica of the golden fertility idol seen near the beginning of the film. Predictably, the Disney idol sold out within minutes, and since then, hundreds of them have been put up for sale on eBay and other sites. Many appear to be for fairly obvious knock-offs, which has sparked much discussion about how to spot an "authentic" Disney prop replica, as opposed to a replica of said replica.14

Paans actually bought a replica of the Golden Idol on eBay, photographed it, and sent it to an artisan. Based on the photo—intentionally showing only one side of the figurine, offering no indication of the object’s dimensions —so it had to be interpreted, it was made into a replica, which was then sent back to him (Paans). This new version was then photographed (by Paans) in the same fashion, sent to yet another maker, and so on.15 Thus, the cultural mutation of the artefact extends as an ever-evolving “meme” that slowly moves away from its prototype while retaining its iconic features.

The (re)appropriation as acted out in Paans’ Case Study IX serves as an indication of how we assign value to works of art and historical artefacts and how our perceptions change unnoticed over time.16 Coming from different countries, each artisan had only seen the maker's photograph before. In the process of reproducing reproductions, the statue is progressively transformed from a screaming, giving-birth woman into a stately lady who seems to meditate, half-naked, in peace —a cultural mutation caused by the maker's own cultural background, ideology, commerce, taste, or available technology.

To emphasise the power dynamics behind such mechanisms, Paans purchased a series of both antique and tourism-oriented Mexican masks, which he then had Spaniards performatively wear (in Spain). Flawed mimicry can thus also be recognised in the hybrid mask culture that evolved from pre-Colombian culture and currently recurs in various outlets, echoing a colonial glitch. This theatrical intervention became incorporated in his case study Conquistadores Masks (VIII), a series of works referring to the complexities in the ways cultural identities form through interaction and exchange.17

Overall, with all these case studies brought together in the book, Paans aims to grant a better understanding of the complex ways through which we (re)produce archetypes and long-standing memes. By showcasing the complexity of networks as stretched over time, our own and non-human entanglement ought to be visible, yet this is complicated by the ease with which forms or representations can deform, continuously transmuting as floating signifiers. At best, as our perceptions will retain a complex foundation of sensory input, cognitive processes and prior experiences, it’s an impetus towards transforming self-limiting beliefs and discovering how we can come to terms with our socio-cultural ecology.18

1 https://www.world-archaeology.com/features/the-bear-necessities/

2 https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cn0g9jv707yo

3 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pareidolia

4 In its original conception, a “meme” was analogous to a “phoneme,” the smallest unit of sound in speech, or a “morpheme,” the smallest meaningful subunit of a word. The British evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins is credited with introducing the term in his 1976 book, The Selfish Gene.

5 Floating Signifiers: Case Studies On Image, Origin and Representation. p7

6 The Killing of the Tree Spirit [Oak Tree 2472], In: Floating Signifiers: Case Studies On Image, Origin and Representation, pp. 35-54.

7 Fredric Jameson, Reification and Utopia in Mass Culture, Social Text, No. 1, Winter, 1979, pp, 130-148, https://www.jstor.org/stable/466409.

8 The Oxford Dictionary of Critical Theory. https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095824238. Ironically, in academia, this proposition by Jameson has been addressed in literature so that it in itself can be considered a ‘meme’ that keeps floating around in the academic discourse.

9 Steven Spielberg, director of the first Jaws movie, decided to mostly suggest the shark's presence, employing an ominous and minimalist theme to indicate its impending appearances.

10 A floating signifier's meaning is still subject to interpretation, while an empty signifier may be completely open to interpretation, even to the point where it is devoid of any fixed meaning.

11 The Löwenmensch figurine is a prehistoric ivory sculpture, 31 cm tall, discovered in the Hohlenstein-Stadel cave in Germany, and dates back between 35,000 and 40,000 years. It is one of the oldest known examples of an artistic representation, depicting a human body with the head of a cave lion and likely holding symbolic or spiritual significance, possibly connected to early religious beliefs or shamanism.

12 This Wiki presents an impressive list of hybrid creatures in folklore.

13 Case Study IX, Panta Rhei. In: Floating Signifiers: Case Studies On Image, Origin and Representation, p. 130.

14 Some of those idols were modelled according to what could be gleaned from watching the movie frame by frame on VHS. Others were informed by information gleaned from careful study of the LucasFilm archives and tidbits that popped up in interviews.https://www.byteside.com/2021/08/indiana-jones-and-the-search-for-authenticity

15 16 Case Study IX, Panta Rhei. In: Floating Signifiers: Case Studies On Image, Origin and Representation, pp. 130

17 Ibid, pp. 113-128.