On Deliberate Tensions and Closeness

Selma Selman deliberately presents herself as an artist with Romani origin, rather than simply as a Romani artist.1 The poverty and social exclusion she experienced throughout her upbringing echoes in her artistic practice, spanning painting, sculpture and performance; unique and personal expressions yet decidedly connected to both contemporary visual culture and art history. She won The Tajsa Roma Cultural Heritage Prize 2025, which embodies Roma pride and honours the outstanding creative achievements of Roma artists and cultural producers across diverse fields.

_xs.webp)

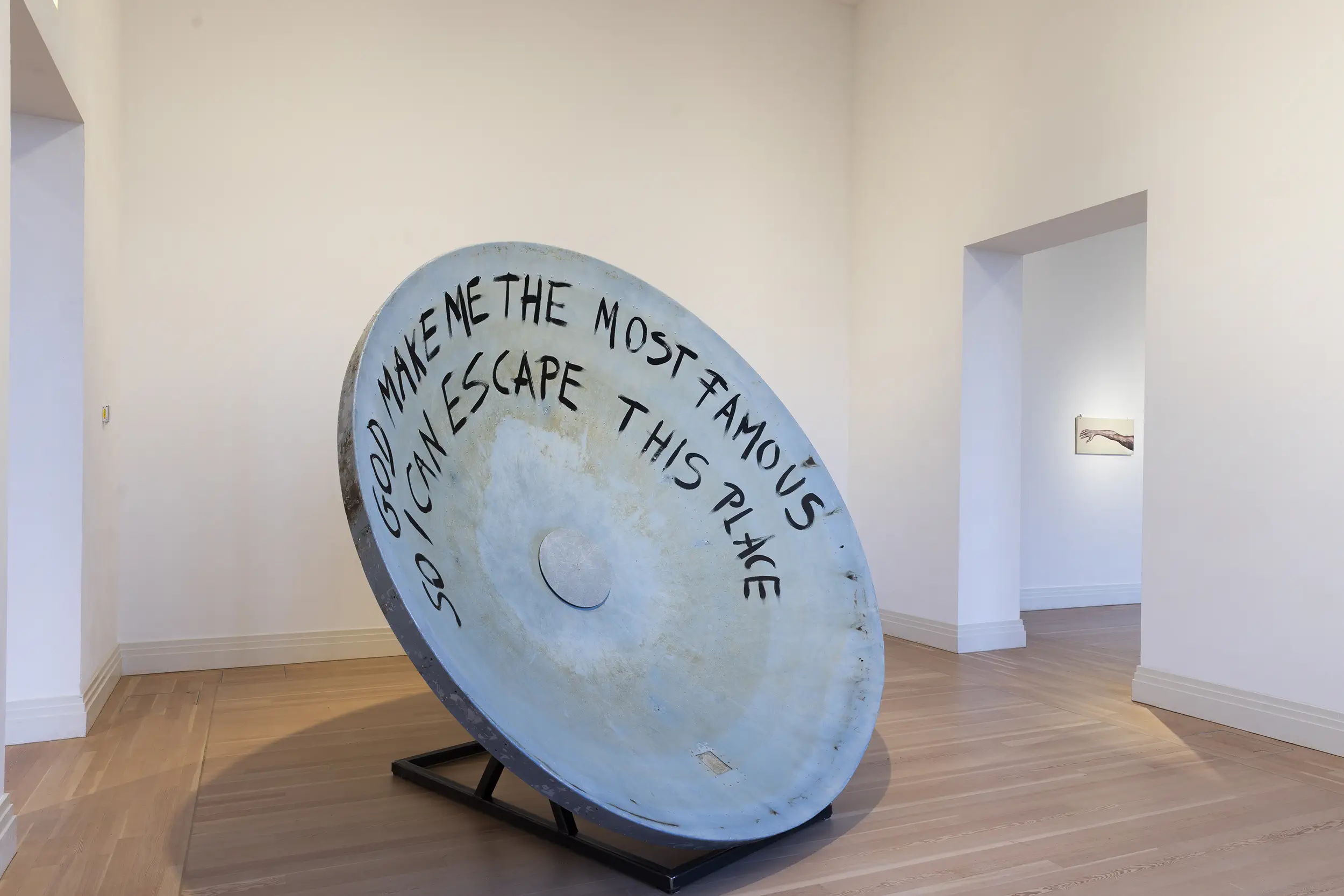

At the core of her practice, balancing on levels of both technical skill and metaphor, are themes of desire and self-determination, through which she critically explores the limits of, and restrictions placed on, individual and collective identity. Poetry and sound are genius elements of her performances too (especially in her feminist monologues directed to a certain Omer).2 Selma’s artistic approach is the extension of her family’s practice: she re-uses elements from the waste yard and applies metal pieces, old rugs and large everyday “things” to paint on and to create art objects with. Supported by her kin, she disassembles electronic waste and recovers the valuable metal, taking up her family's economic activity in order to highlight the sustainability found in often undervalued forms of labour, such as gleaning and recycling.

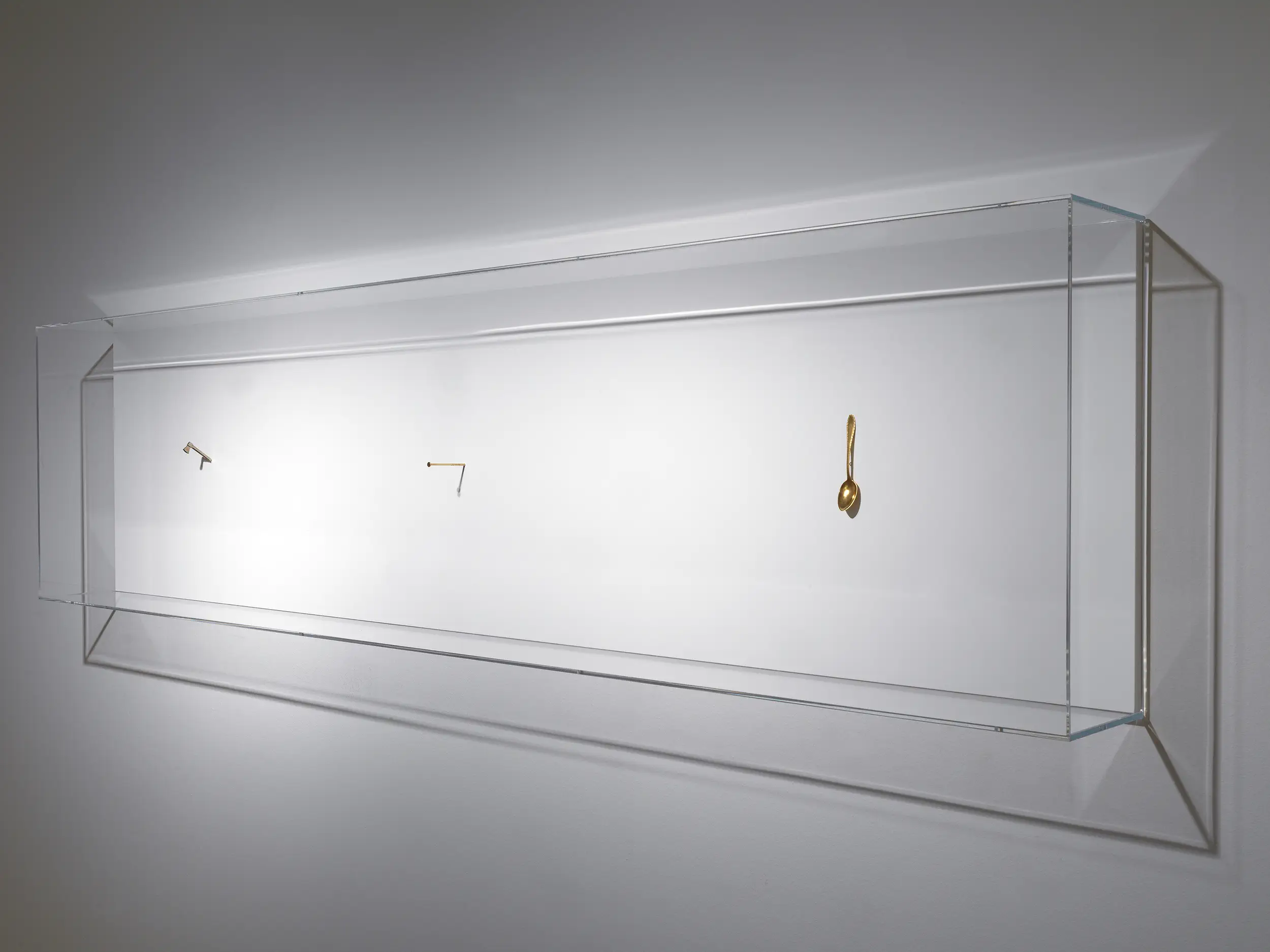

For the opening of her exhibition at Gropius Bau in Berlin, November 2023, Selma presented Motherboards, an ongoing performance in which she extracts gold from scrap metal, assisted by her father Hajrula Selman, relative Muhamed Selman, and neighbour Meho Husic. With hammers and drills, they opened the computer motherboards that had been gathered in the museum gallery. They extracted the gold, a material that evokes both desire and destruction, and left the dusty motherboards on the floor. The noise produced during the process was transformed into a musical composition through collaboration with DJ and producer Dauwd and cellist Boram Lie, with Selma scanting poetry in between the dismantling.3

Selma developed a special technique to make gold morph into new objects, and the performance at Gropius Bau even engaged with the historical opulence of the building itself, pointing to its gold ornamentation. Thus, the performance reflected on how value is created within the art market, as the recovered gold at Gropius Bau was turned into a sculpture: a golden nail.4 Furthermore, the sounds generated during the performance were based on a frequency drawn from Berlin's musical heritage, which is shaped by industrial soundscapes.

I was Head of the Curatorial Department at Gropius Bau at the time. Selma and I have known each other for years, and regularly work together. Most notably, we developed her0 (2023), Selman’s largest solo show to date.5 On the invitation of OVER Journal, what follows is an insightful transcript of a moderated conversation we had back then.6

Zippora Elders [ZE]: What was it like for you to perform in Gropius Bau, this historic building in the middle of Berlin?

Selma [Selman]: I feel very humbled and emotional. It was the biggest challenge ever. I mean, it was amazing to work with this kind of institution, but it was also very challenging. I came to Berlin on the 7th of October, and I was, to be honest, emotionally destroyed.7 Still, I had to keep up with making the work and thinking about what’s next, with what to expect from myself and what people are going to expect from me. I decided that I’m just going to do something that I believe is a good thing, saying something about humanity and about what we have in common. Or at least about something that can be communicated to many of us. In my humble opinion, I do have a lot of things to say, and I do like to communicate with people coming from all sorts of backgrounds.”

ZE: When you talk about topics such as displacement, belonging and migration, it also reflects back to your family. Your father, your brother and your neighbour are taking part in the iconic Motherboard performance, and it made me wonder: what are we even doing, working together as curators and artists, when the work itself arrives from such a tight family bond?

Selma: I’ve worked with my father since I was 17. He was my manager when I was operating as a commercial artist. We live in a patriarchal world, and as a woman, I had to fight through all these layers of patriarchy. I had to prove that I can be as strong as a man. My role model when I was young was my father. But once I learned what it means to be a strong woman, my mom became my role model, so that shifted.

ZE: Indeed, your mother’s and father’s practices are here, too, in a way; your work evokes how they survive but also how their labour lives on in an exclusive, elitist art space.

Selma: Roma people understood sustainability before recycling became a common thing. Hundreds of years ago, they started recycling not only metal, but all kinds of things—make living from that. I think that’s so powerful! Western society only started to do that recently, so Roma people are futurists in that sense.

Now, I actually have a question for you, Zippora. Knowing about my background, being familiar with my statements, and that I can be kind of easy-going to work with, but also that I won’t sign off on certain things, knowing all these layers and deciding how you’re going to position me, how was it for you to work with me? How was your experience? It doesn’t have to be positive, ha ha.

ZE: I’m very interested in this power of transformation in your work. In your practice, we witness how you make what you find on the scrapyards into art; how you bring dirt into the museum as a huge, monumental object—in a way reminding of a work by a male, American Abstract Expressionist painter—and exhibit it here, in the gallery space. It felt like a force of transformation when we were making this presentation.

Selma: People sometimes approach my work like it’s garbage and carelessly hit it with their foot and shoe. But I’m the only one who has the right to do that, right? I’m the only one who can say that that’s garbage. When I make a hole in my painting. I expect people to consider it art. Because it is. Something similar applies to the people I collaborate with, who I belong to. I’m the one who decides that I am to be identified as a “gypsy”. Someone else, from outside my closest realm, is not allowed to address this.

Earlier this year (17 May-August 24, 2025) Selman presented her new exhibition 600 Years of Migrant Mothers, a solo show tracing her female ancestors over six centuries, aiming to give visibility to the often overlooked women.8 It features a series of monumental new paintings alongside a selection of films, drawings, and sound works. The project is part of a larger artistic research into the women who shaped her life, while (too often) remaining invisible in history. By blending real and fictional elements to reveal stories lost across generations, places, and languages, she explores the link between knowledge and power. Who gets to know their foremothers? And how does that knowledge translate into political agency?

Supported by feminist and historical research, Selma reconstructs female genealogies within marginalised Roma communities in Southeast Europe, where male lineage is traditionally prioritised. I asked her how this highly personal and reflective ongoing project connects to her increasingly exposed and sometimes spectacularised work in the current leap of performance art in the contemporary art field.

Selma: Working on and presenting this project in Friesland (NL) felt grounding and intimate—almost like a return to the core of why I create. The setting allowed for vulnerability, without the overwhelming noise that often surrounds institutional or art fair contexts. It gave me space for slowness, reflection, and time. Yes, I could truly think and spend time with my work and I even slept in the same house where the show is held. It felt like I was sharing the most intimate part of my art—if someone wanted to know my soul, they could see it in that exhibition. The entire installation became part of the house itself, and the house, in return, became part of the work.

At the same time, I’m very aware that artworks—including my own—can circulate in high-profile settings, where performance is increasingly instrumentalised or aestheticised to serve institutional narratives. That is the pure mechanics of the art market, but audiences, targets, and expectations are still mine, essentially. Even so, whenever I perform or present artwork in bigger institutions or fairs, I make sure that it comes from my guts—I give myself one hundred percent, always.

Obviously, there’s a tension: the intimacy and urgency of a performance can easily be diluted or misunderstood when it becomes a spectacle. So, while I’m grateful for visibility in larger contexts, I remain protective of the emotional and political weight of my work—especially when it stems from personal or embodied histories. What I did here, in Friesland, reminded me that the most meaningful encounters often happen in spaces that are quieter, slower, and more human in scale. At the same time, I’m grateful that I can work in both kinds of environments—the one that offers care, and the other kind that demands resilience. Why? Because I truly believe in art.

If anything, Selma Selman’s latest work is exceptionally contemporary: through lived experience and political insight, it is consciously committed to giving voice to and making visible the presence, cultural contributions and labour of migrant women in particular and therefore migrants—all children of mothers after all–in general. For me, and especially now, that is incredibly meaningful. It breathes the values in which we found each other as fellow daughters, art workers and friends.

1 “Until only a few years ago, my friends would make fun of my Bosnian-English accent and hybrid use of language yet none of them could really grasp that my native tongue is Romani,” she recalls in one of her performances.

2 See Selma Selman: Letters to Omer, recorded June 15, 2025 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HMzT4F3scUY

3 Motherboards was performed again in January 2025, at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam—in collaboration with ABN Amro (a major Dutch bank) for a limited invited VIP audience. Clearly, these circumstances exposed a certain tension between an “elite” artworld driven by exclusivity and Selma’s practice, as it is inherently and radically about breaking that frame.

4 This sculpture was later shown at Schirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt and the Stedelijk in Amsterdam.

5 https://www.berlinerfestspiele.de/en/gropius-bau/programm/2023/ausstellungen/selma-selman. Here I also wish to acknowledge the work of Amila Ramovic, the first curator to work with Selma (beyond her family) who arranged her solo exhibition in Sarajevo.

6 As transcribed by Zippora Elders, Summer 2025. Longer version of the conversation about her0. Z. Elders and S. Selman. Transforming Noise and Holding Space. January, 2024. https://www.berlinerfestspiele.de/en/gropius-bau/programm/journal/2024/transforming-noise-and-holding-space.

7 Selma refers here to 7 October 2023: a surprise attack by Hamas against Israel, involved a multifaceted assault utilizing rockets, drones, and ground incursions, marking a significant escalation in the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict.